|

|

Said

Soe

a conversation with

San Francisco videomaker

Valerie Soe

by

Anita Chang

|

|

|

| In

early 1990s San Francisco, as I was convalescing from my years living

in the Big Apple and anxious to clear the mirror, Valerie's video

works provided just the right kind of medicine I needed to recover.

They reminded me of the Chinese herbal concoctions my mother used

to brew at night when I was a kid — concentrated, yet with

a scent that was hard to escape, bitter to the bone yet cathartic

at its conclusion. As I've gotten to know Valerie, she's not only

become a role model, mentor, and friend, but a supporter of my own

media work. Although she has less time because she's been busy raising

her baby girl, Rose, I was quite honored to have a piece of her

alone time for this interview on November 14, 2001.

|

| Your

works and writings have always had strong political content. How

have the events of 9/11 affected you and any current works of yours?

When I used to make this politically charged work, I was very

sure of what I thought. I had a very definite point of view, knew

exactly what to think based on my political beliefs, social convictions,

Marxist upbringing, and NOW, I'm not quite sure what to think. It's

very easy to say that the U.S. is this global imperialist power

that's stepping on everybody, which is certainly true; bad things

are happening, and the government is doing bad things in my name.

But at the same time, you can't sort of let people blow up buildings!

I wouldn't go to war about it, but there should be some recourse.

People are trying so hard to put meaning into something that in

the U.S. they didn't have to think about, except in a very abstract

way. They live in their middle-class existence, in their safe haven

of the U.S., and then all of a sudden they're physically threatened

and it has changed the way they think. So again, there are some

things that never change—the way that the mass media parallels

what the Pentagon says.

What does your media research usually entail?

Doing internet. I go to alternate sources like the British, leftist

papers, the Guardian in England. Friends funnel me inflammatory

articles that don't necessarily get covered in the (SF) Chronicle

or Channel 7. For example, the U.S. has ceased all satellite reporting

of any of the military action over in Afghanistan, bought all the

satellite pictures off there and forbidden the media to use the

pictures. It's all open knowledge but not written about in this

country.

The internet is making a difference because people are able to send

information around. They're bypassing mass media and communicating

person to person. You can send out 50 spams to your friends you

download from another press source from the web. There's a lot of

conspiracy theories going around and a lot of misinformation, but

there's also really good stuff out there if you're willing to look

out for it. So I think that has tempered the coverage. I'm sure

the government is worried about that and wants to restrict that

somehow. I think in the so-called Patriot Act there's a provision

that if you hack a government website, then that is an act of terrorism.

I'm not sure about that, you might have to check. So they're really

cracking down on a lot of this stuff. I wrote an email to my friend

in HK that we're not getting much information through the mainstream

media but that I can go on the internet and look for stuff. And

then I thought, Jesus, I sound like I'm in China, like communist

China, because China blocks websites and they know that's the way

people organize.

You've often referred to yourself

as a cultural worker. Could you discuss this in the context of you

being Asian American and of the events (referring to 9/11)?

I would say about 70–80% of my works deal with Asian American

themes, and I see my works as an alternate voice for dissent, you

might say. The internet has changed all this because it's more efficient

to send out an e-mail instead of, "Let's make a film or video."

But in the '80s, it was more efficient to make a movie and show

it around because there really wasn't the web, so that was becoming

the way that people were electronically leafleting, sending out

alternate voices. I have no time, so I just forward e-mails.

As an experimental videomaker, do

you feel you have a place to show your work and that it's reaching

the intended audience?

In San Francisco there are venues for my works: ATA (Artists' Television

Access) shows stuff, and the Cinematheque.

But do you sometimes feel you are

preaching to the converted?

But sometimes it gets on TV, like the local broadcast Women of Vision's

NAATA (National Asian American Television Association). They distribute

to schools and package films together for corporate sensitivity

training.

I'm in the same situation of making

experimental documentary works that get very little distribution.

Do you have any suggestions as to how that could change?

I noticed recently that the younger Asian American filmmakers are

making narratives — commercially accessible with the same underlying

issues of identity, culture, and politics. And it's neat because

you would think that an agitprop documentary would be more powerful

and have more impact, but if a tree falls in the forest and nobody

hears it, right, it's the same thing. So you get a movie out there

like The Debut (a feature film about the Filipino American experience

that got amazing theatrical distribution. If you want to know more,

check out http://debutfilm.pinoynet.com)

that is reaching out to all these different people, and being shown

in multiplexes in Virginia and southern California and so forth.

I think they made a million bucks, which is great, low budget, took

eight years. They're reaching regular people. Maybe that's the way

to go. No, I'm not making feature films, but I support people who

do. I think it's cool.

Let's go back to the beginnings.

Who was your inspiration or role model?

When I started to make experimental films, there were not that many

Asian Americans doing it for sure very few people of color. Marlon

Riggs I really liked because he was doing really politically engaged

work that was also formally interesting, like Tongues Untied. I

also used to tell people I started out doing the punk rock thing,

which is very do-it-yourself, which was like the early '80s. The

idea that you didn't (a) have to spend a lot of money, (b) go through

commercial channels or make commercial work, and (c) make work that

was appealing to a mass audience. You could be very iconoclastic

and individualistic and still make good stuff, and that was kind

of fun. So I think I was really colored by that when I was younger.

This idea of having the counterculture, alternative underground.

I grew up in the suburbs, too. I didn't know that many Asian Americans,

although in college there were a lot of these (Asian American) leftists

working in UCLA when I was an undergrad, and they imprinted me with

their radical beliefs. They were starting to realize they could

infiltrate academia and shape young minds to be communists or socialists.

Nowadays there seems to be more Asian American artists. It's really

great and encouraging. If you go someplace like Locus (Locus is

an alternative arts exhibition and performance space in Japantown

run by a group of young Asian Americans): an important component

to their exhibitions is to create in-depth dialogue with artist

and audience. To see all these cute young Asian Americans together

... they're so earnest and interested. They're smarter than I was

in a lot of ways.

What advice would you have for young

Asian American artists who want to make films?

It's great to live in the Bay Area because there is a network of

support. In Los Angeles, media art support is dissipated, very spread

out. Anywhere you can get people to help you out and be supportive

and let you know it's okay to do what you're doing is really important

because there is not much financial reward, there is no fame. The

Film Arts Foundation ad campaign is great because it says things

like, "It's not for the money, or the glory or the fame, it's

for the love of film." Right, which is true, and it's kind

of pathetic. You can't be doing it for any other reason. Just make

sure you have a support network.

What's

it like being a Mom now?

I thought of Kelly Loves Tony (a documentary film by Spencer Nakasako,

maker of AKA Don Bonus, about a young teenaged Laotian couple's

struggles), and now I understand how difficult it was for her. You're

always tired, that's priority. There's some weird biological thing

that goes on where it's easy to mommy mom when you have a kid. That

is the first thing you think about, the well-being of the kid. So

to concentrate on something else like art, which actually takes

a lot of concentration, it is really hard. You only have so much

energy. All I can say is that I'm really glad I have this editing

thing on my computer. Even if I don't get anything done, it just

makes me feel I'm keeping that part of my brain alive. Not letting

it atrophy. It's really hard.

|

Check

out

Valerie

Soe's

work online

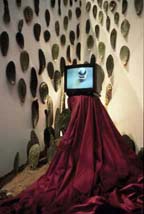

Binge,

1995, bullet casings, monitor,

altered target

Binge,

1995, KFC zoetrope,

altered makeup mirror

Walking

the Mountain,

1996, installation view

Valerie Soe

has made numerous award-winning videos. Her video pieces are:

ALL ORIENTALS LOOK THE SAME (1986, 2 min), Scratch Video

(1987, 4 min), New Year, Parts I & II (1987, 23 min),

Black Sheep (1990, 6 min), Destiny (1991, 6 min),

Cynsin: An American Princess (1991, 10 min), Picturing

Oriental Girls: A (Re) Educational Videotape (1992, 12 min),

Beyond Asiaphilia (1997, 14 min). Her works are distributed

by IDERA, CrossCurrent Media, Women Make Movies, Video Data Bank.

Installation works are: Diversity with Chan Cheong-Toon

(1990, 3-channel video installation), Heart of the City

(1992, 2-channel site-specific installation), Mixed Blood

(1992, interactive video installation), Risk=Fear+Need

(1994, participatory performance), Walking the Mountain

(1994, video installation).

Soe has been a recipient of the James D. Phelan Art Award in Video,

a 1994 Cultural Equity Grant from the San Francisco Art Commission,

a 1994 Art Matters Fellowship, and a 1992 Rockefeller Foundation

Intercultural Film/Video Fellowship.

Soe also writes art criticism and has been published in Afterimage,

High Performance, Cinematograph and The Independent,

among others. She curated the exhibition Girl to Woman: Stories

for the New Feminism at the University of California, Irvine's

Fine Arts Gallery and has programmed several shows at Artists'

Television Access and the San Francisco Cinematheque on teen videomakers.

She is also on the Board of Directors for the Film Arts Foundation

and is a founding member of X-Factor, an experimental film and

videomaker coalition. She chairs the Film/Video program at the

California State Summer School for the Arts and is on faculty

at San Francisco State University's Asian American Studies Department.

In addition to a 9/11 video project, Valerie Soe is currently

working on a longer personal documentary, The House of Ong,

about trying to locate the site of her grandmother's house in

Phoenix, Arizona, which she describes as "sort of a surreal

and humorous journey since it was torn down in the '70s to make

room for the superhighway that now bisects the city."

|

| What

are some of your thoughts on the world as you raise your daughter?

The new economy was booming and everybody seemed so happy, in a

lot of ways and carefree. That was an amazingly euphoric time period,

even though we were grumbling about our rents and SUVs and all that.

You mean euphoric in terms of most

Americans?

Well, in San Francisco especially. I think that's why a lot of people

had kids in the past year because they had that sense that things

were doing really well. But, anyway, things are getting worse. It

seemed more optimistic back then, and now it's reversed. But at

the same time, when you get to be older, you realize that things

are going badly but then they'll get better again, right? I read

that about older people who are in their seventies. They say, "Well,

we lived through World War II and we saw the '50s and '60s and we

know that it was a terrible time, but it will change, hopefully."

So I try to be optimistic as much as I can about that. Even though

I make stuff that is very pointed and critical about society, I

think I'm actually an optimist at heart. That's why I probably bother

to complain, because I think complaining will actually change something.

I think people who are pessimistic who don't think they are going

to be able to change things, they just live and they just are depressed.

What

are some of the things you think have changed since you started

your work as a videomaker?

Actually, I think the world has gotten worse in some ways, like

rampant consumerism. It seemed like after the World Trade Center

thing, for a week or two, people were actually thinking about deeper

values. Oh my God, how can we change our lives? How has our consumerism,

or our greed, or self-centeredness made this happen?

And that's where media literacy is so important because so much

of media is what directly fuels consumerism. That's what I do. I

teach in my class how to read things critically, how to analyze

the stuff that is coming at you, and once you learn it, you can't

NOT see it. That's the interesting thing, once you learn to dissect

imagery, then it's sort of a skill that you keep. It's really good.

I am encouraged by that. That's why I like teaching in Asian American

Studies, because lots of students don't come from critical theory

or an art background. They learn to read the media and watch films

they don't usually get to see. Plus they don't see that many Asian

faces in movies.

What is the kind of creative work

that you really like doing?

I used to do installations just so I could get the gallery shows,

but I don't really care about doing them, because I don't think

I'm really good at it. I guess I like making personal stuff, where

I get to talk about my personal problems, couched in humorous terms.

These longer pieces are hard for me to do — anything longer

than five minutes. It's just too big. It's formless and amorphous.

And when you talk about your family, you have to be very careful.

It's harder. I'll never do it again. I have to finish it, because

I made it a project for this Rockefeller thing and (Rockefeller)

thought this sounded like a good project and I probably would never

have made it if I had never gotten that grant. That is the problem

with these big grants, people make ambitious proposals that they

can't necessarily complete.

What does it mean to really survive

as an artist in San Francisco, WITH integrity?

Well, when I started making videos, there were still a lot of smaller

grants that supported experimental forms, like the Western States

grant, FAF (Film Arts Foundation) is one of the few small grants,

and Creative Capital. You would get these little grants for personal

works and there was a period where all these things went away —

AFI (American Film Institute), Western States, CAC (California Arts

Council). All that were left were the NAATA grants, you have to

aim things toward public TV, which is not my style, but you have

to adapt your work to fit these grants. That is why it's hard for

someone like me who is not used to making longer, more professional

films. On the one hand, you want to get money, live off it if you

can and a lot of people do it and they can do it okay, but on the

other hand, it affects the way you make work, so it's hard. And

you want to think you can make a living and somewhat support yourself

through these grants, but it is actually really hard, nowadays especially.

As far as the teaching goes, there is not that much teaching out

there. You have to calculate what the market wants from you, and

that is true of anything you're selling I guess, whether that is

yourself or your films. You see, it's capitalism's fault again.

What I like about your work is that

it is not only intelligent but also really accessible. You've struck

a nice balance between formal experimentation and also incorporating

everyday, recognizable pop iconography.

'60s and '70s experimentation was all about expression, not reaching

out to audiences. So you get Michael Snow and Brakhage, who are

hard to penetrate. To me, I was more interested in getting people

to watch it. If nobody watches it, then why make it? For your own

gratification? It's important to have the audience as your partner.

Political agenda couched in accessible terms, digestible terms.

That's sort of the trick too—to get people to absorb something

they might not normally absorb because they are seduced by the way

that it engages or entertains them.

How do you see being a "cultural

worker" as someone actively involved with social change?

I always believed that doing media work was just another form of

activism, because the way we get most of our information is through

TV, advertising. So going out and picketing and protesting is fine,

and I've certainly done that but it's not necessarily the most efficient

way to reach a lot of people nowadays, partially because the establishment,

the powers that be, realized that if you just ignore protesters,

then they don't exist. If they're not on the TV news, then they

don't exist. It really hit home for me during the Gulf War because

there were huge massive demonstrations in San Francisco and that

got no coverage. I thought, wow! they just pretend that it did not

exist. So that meant to me that there ought to be another strategy

to reach people. It is partially why I work in media, which is to

use another form of reaching people. As Craig Baldwin says, "Speaking

in the present tense nowadays, which is the filmic language."

Do you vote?

Oh yeah, always; it's one of my favorite things to do.

Valerie

Soe

has a short film included in the "Underground Zero/9-11 Project"

(organized by independent filmmakers Jay Rosenblatt and Caveh

Zahedi) which is currently showing at selected theaters in the

Bay Area. A powerful and moving collection of thirteen short films

inspired by the events of September 11. |

BIO

Anita Chang is a San Francisco-based

filmmaker whose works have screened nationally and internationally,

won awards, and been broadcast on public television. Her works include

She Wants to Talk to You (29 min, 16mm, color, 2001), Imagining

Place (35 min, 16mm, color, 1999), Mommy, What's Wrong?

(1997), One Hundred Eggs a Minute (23 min, 16mm, b/w, 1996),

Video Letter to the President (1996), and Spofford Alley

(1994). They are distributed by Third World Newsreel, National Asian

American Television Association and Berkeley's UC Extension Center

for Media. She guest lectures, curates and writes on film, and teaches

film and video production, alternative documentary and experimental

filmmaking. She was an artist-in-resident in Kathmandu, Nepal, where

she taught "Alternative Strategies in Documentary Filmmaking,"

and she has recently completed a residency at the Headlands Center

for the Arts. She is currently education director at Teaching Intermedia

Literacy Tools, a grassroots organization which brings media literacy

education and media production to youth in schools and after-school

programs.

Special thanks to Steve Gilmartin for help in copyediting this interview. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|