Walls

with Tongues: Muralist RIGO 02 Speaks

by

Siobhan Fleming |

|

| If

you have spent any time in San Francisco’s South of Market

District, you have probably seen Rigo 02’s artwork. The San

Francisco-based muralist has done several enormous murals there

in his characteristic style of simple bold graphics combined with

one or two words, including One Tree next to a freeway on

ramp, Innercity Home on a large public housing structure,

Sky/Ground on a tall abandoned building, and Extinct

over a Shell gas station. Competing with all the surrounding commercial

billboards which tell you what to think and what to buy, Rigo’s

work instead invites the viewers to stop, reflect and figure out

their own messages and meanings to the simple signs. This is what

public art is all about.

Ricardo Gouveia goes by the name Rigo 02, having formed the name

"Rigo" in high school to hide his identity in an underground

zine that he was involved with and changing the number behind the

name annually to reflect the current year. He came to California

from Madeira, a small Portuguese island off the west coast of Africa,

to study art in 1985. Influenced by American pop culture and the

political climate of change in his own country during the 1970s,

the 35-year old artist got his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute

in 1991 and his MFA from Stanford in 1997. Over the past 16 years,

his work has included over a dozen one-person shows and participation

in many group shows in San Francisco and in far away places such

as Mexico, Taiwan, Chile and Europe. His involvement in the Bay

Area mural scene has been passionate and important. In 1993, along

with Aaron Noble, Rigo founded the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP)

in the Mission District dedicated to free form murals using a varied

array of mediums such as spray can, graffiti and stenciling. He

has painted murals in Balmy Alley in the Mission District and several

years ago finished a giant ceramic tile mural for the new international

terminal in SFO entitled Thinking of Balmy Alley. He won

SFMOMA’s Society for the Encouragement of Contemporary Art

(SECA) award in 1998 and produced both indoor and outdoor murals

for that project.

If his style of using everyday symbols and straightforward graphics

tends to be simple and direct, the possible messages and issues

of his work are anything but that. To paraphrase Rigo, his art aims

at mentioning the invisible; to make light of things that are all

around us, but often go unseen. It is this questioning of our realities

and offering opportunities for social dialogue and examination that

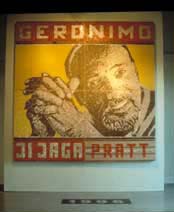

makes his murals so powerful. Among some of his most significant

work, he cited several projects with American political prisoners

Geronimo Ji Jaga (Pratt), an ex-Black Panther exonerated after serving

27 years in prison and Leonard Peltier, a Native American artist

and activist who many consider unjustly imprisoned since 1977.

Interviewed at the end of November 2001 in his Outer Mission studio,

Rigo 02 had just participated in two New York City shows including

Marked-Bay Area Drawings in September at Hunter College in

which several of his Lost Bird flyers appeared and at Widely

Unknownat Deitch Projects in November. Soon after, he was heading

to Taiwan to show his work there in a container arts festival which

has since taken place. The interview begins with a discussion of

his recent work, followed by his background, murals in San Francisco,

politics and the future. |

| Recent

Work

You just came back from New York

where you participated in the show Widely Unknown. Can you

talk a little bit about that?

The show was an exhibit curated by Eungie Joo and it was

mostly Bay Area painters. The show was sort of centered around the

work of Margaret Kilgallen and her recent death [Kilgallen, a San

Francisco-based artist noted for her murals and paintings died in

June 2001]. It was a bunch of her peers from here and some of the

people that she had met in other cities where she had worked. Barry

McGee was in the show as well, Chris Johansen, and several others.

We were sort of living in the gallery 24-7, setting up and staying

there with the other people involved. It was a special time and

it was also representing what they saw as somewhat of a West Coast

movement. I had one drawing specifically for the show of a moonscape

and it had a rhino which is pretty much a replica of a Durer drawing

from the early 1500s. It was sort of addressing some millennial

or end of the century ideas.

Why the rhino?

Well, there’s a story of a rhino and the first sea voyages

of the Europeans to Africa, to Northern Africa, which was done by

the Portuguese and the Spaniards. I’m from Portugal and there’s

this story that they [the Portuguese] were there in this boat and

they had never been that far south nor had had contact with people

from there before supposedly, and they see this animal that they

have never seen before. The rhino represented this monster that

was not really part of their world view, so they decided to capture

one and bring it back to Lisbon to show people. They manage to bring

it back alive and the story goes that Durer comes down from Central

Europe to render the rhino because he was the best scanning device

at that time, the best renderer. But then, judging from his drawings,

you start to dispute whether he did in fact see the rhino and it’s

a pretty fantastic drawing. Chances are that maybe he did not see

it. Also, the Portuguese would carry these stone markers, pillars,

with the insignia of the kingdom and they would prop them up in

these new far off places. So, I was making a parallel with an American

flag on the moon. It was this other worldly creature showing up

in this other place where people like American astronauts have been.

The underlying thing is to what extent does the dehumanization of

the unknown, of the other, go on. It’s called Lunatics and

Other Imperialists.

What about the Arts Festival in Taiwan in December that you are

participating in?

The project that I’m doing there is called TheTricycle Museum

and it will be part of this container arts festival. Basically,

these shipping containers will be transformed into the initial modules

that could be like nomadic, modular shanties where the container

will double as the exhibition venue. This museum will document these

tricycles that are manufactured usually in small numbers or that

are actually unique: the person that uses them makes them. I think

they are depositories of creativity, ingenuity and resourcefulness.

I think they are very aesthetically pleasing, telling and very humane

in a way that I find more appealing than high end technological

machines, like the Mercedes and the Porshes which seem to play a

big part in this male fantasy of what success might be. And then

there’s the fact here in the United States and the West Coast

in particular of the whole low rider culture which I also find very

interesting with cars that have been highly fetishized and decorated.

I think that these tricycles possibly can receive the kind of investment

and fascination that the low riders have. It’s propping the

tricycles up with star status as vehicles and as objects.

And are you going to have tricycles from different countries that

are going to have different uses?

There is documentation, photographs and drawings, of tricycles for

a few different places. First I have documented some myself, but

now I’m already getting people who tell me they also have photographs

and such, so we’ll add those as documentation. The Tricycle

Museum there is the seed of what could be a larger project which

might not happen. I think it will have sort of a utopian, sort of

fantasy side to it. The way I see it, after Taiwan, it will go to

Cuba next and then in Cuba, it will be joined by another container

and then from there, it will go to India and it will be this space

station with different modules which are all sort of economic low

end. So whether that dream will have a further life at all or not

is beyond me at this point. But I’m very interested in a decentralized,

nonhierarchical world view, so this idea of different peripheries

communicating and exchanging ideas without having to go through

a center is exciting. I’ve documented the tricycles in Cuba,

which like Taiwan, is an island. Taiwan is the border now geopolitically

between the United States and China. And Cuba in a way was the border

between the United States and the Soviet Union. I find them two

interesting island countries. I would like to have communication

happen through this very unsuspecting item of the tricycles. My

role as an artist amidst all that I guess is not clear. I feel like

I’ve become an outsider to most places you know, even to where

I’m from which is Portugal. I came here when I was 19. I’m

obviously very much integrated in life here, but I’m also not

fully from here, so there’s potential for complicated things

with tourists and voyeurism and colonialism, but I’m just embracing

all this and trusting my instinct and then how ever those things

manifest, hopefully they’ll be interesting. |

|

Lunatics

and Other Imperialists (2001)

Tricycle

Museum, Kaoushung, Taiwan (2001)

Inside the Tricycle Museum

Tricycle Museum

|

| You

stated in another interview that you feel like you are not really

in place A or place B, but that you really reside in the gap between

two places, like an outsider in your life here in the U.S to some

extent and also when you go back to Portugal. How do you feel that

affects your art and does that give you a chance to see things from

a distance?

It makes me appreciate stuff more. I’m growing more contemplative.

The chance of changing location really allows for the regular daily

life of the city to be spectacular. So it’s nice to see an

hour and a half of condensed intense fiction about a place, but

the experience of moving through that place can be just as exciting.

If you don’t know it, you can’t pretend that you do. And

in a place like Taiwan, it’s very hard to pretend I’m

from there.

No one is going to mistake you for being Taiwanese.

Right. Nor can I read the text, but I try to go with it. Now the

tricycle is a good metaphor for that. It’s not the two-wheeled

kind of form, but it’s this hybrid. So in a way, it is a tribute

to madness which is quite distanced from aspirations of a pure anything,

the pure race or pure culture or pure nationality. It’s part

bicycle, part color, part motorcycle. But I find that very inspiring,

and the fact that they are most of the time really a labor of love.

You were also involved with the Depois

dos Cravos [meaning After the Carnations, an arts festival

featuring new work from Portugal ] exhibit at the Yerba Buena Center

last summer/fall?

My involvement with that was more facilitating the contact and the

communication between people here and the artists in Portugal. It

was quite interesting because a lot of artists in the show I did

not know because they are already part of a younger generation and

again it was one of those loose moments where I got introduced to

practically a generation of artists from Portugal in San Francisco.

So it was really like a gift that I would meet them here. It was

quite interesting some of the conversations that ensued. They were

asked if they felt any sort of binding cultural identity among them.

The tendency was not to. There was someone who said he thought the

work that I had done here was sort of more Portuguese than the work

they were doing over there. Again it was this influence of specific

experiences that we shared growing up.

|

| Getting

Started/Early Influences

You grew up in Madeira and you came

to California when you were 19 to visit relatives and then you started

studying art here in San Francisco. I read some articles where you

said back in Madeira, comics and American pop culture had an early

influence on you. Can you talk a little bit about that? Were there

specific comics that you were reading or specific elements of pop

culture that were affecting you, like TV or movies?

A lot of TV. TV was in its first steps then. My parents rented a

TV to decide whether they wanted to buy one or not. They rented

it for the weekend to try it out. There was only one station and

it closed at like 11 p.m. or midnight. I remember that we turned

it on and the first thing that came on was Bonanza. It was

about 1973 or something, in my grandma’s bedroom.

The comics I think was more the form, the possibility to tell a

story. I started drawing comics as a kid. I got exposed mostly to

mainstream stuff like superhero comics and Disney and then some

Latin Americans like Mafalda and then more underground, more urban

expressionist sort of French and Italian comics. And then Crumb

and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers of San Francisco, Last Gasp

and all that. So when I came here I was quite excited about all

that history. I started making comics in high school and did some

zines with other students and some poster art and comics and mixing

of text and image. It was something that I was turned on to early

on. The last couple years of high school, I was hanging out with

this other guy who was a historian and poet, Antonio Aragao, and

a lot of what he wrote about was how the eye did not discern image

from text, how the eye perceives them the same and the eye did not

need more text to make it more literature nor more images to make

it more art. The eye wants what’s open and so in my work, text

started drifting off into speech bubbles and they would start having

volume and leaning against the word and things like that. So I was

very self-conscious from early on because of this guy. It wasn’t

like there was a big pool of kids to work with there. It was sort

of a lonely endeavor. So that’s pretty much how that experience

went.

And did you do murals before you

came here or is that something that you got into here in San Francisco?

What was your first mural and how did that affect you?

Murals started after I came here. When I went from Madeira Island

to Lisbon, there were a lot of political murals in Lisbon. I went

there in 1984 and 10 years before, there had been this big social

change there [the end of several decades of dictatorship and isolation].

There were still a lot of political murals around that were very

exciting. They were big paintings out on the streets. How could

that not be exciting? And then I came to San Francisco and then

I was really exposed to a whole other thing I had never seen. Some

were art murals that weren’t about a particular political message

necessarily. It was just art up there and that was super exciting

to me. I was here in 1985 and I met some people at ATA, Artists’

Television Access, which at the time was on 8th and Howard. They

asked if I’d like to do a show here. A show in America? And

I was 19! I thought it would be great, but I didn’t have enough

money to buy the canvases for the show. Marshall Webber, who was

one of the founders of ATA, worked at a club called Club 9 which

is now the Stud on 9th and Harrison, doing art events. I guess that

was in the mid-80s, so that was back at a time when there was a

lot of interface between the art world and night life, so he set

it up where I would paint a mural for the nightclub, get paid for

it and use that money to buy the supplies. The imagery was just

very much derived from comic books and stuff. The building had nine

windows and I had to use the windows in the design. It was done

in time for New Years, 1985. I wasn’t old enough to be inside

the club, so I was waiting on the outside. That was a great, lucky

situation.

And were you hooked on murals after that?

Pretty much. It was a really nice experience. Some guy stopped and

asked if I needed help, which I did, but I couldn’t pay anybody.

But, this guy came back the next day with his own brushes and he

helped me paint for a few days and we’re still friends sixteen

years later. The whole thing was pretty nice. So that was the first

mural experience out on the street.

What artists have impacted your life and your art?

Many really and at different times. The music that I listened to

and because of the period that I grew up in Portuguese history,

I was always driven to cultural output that had a side of protest

and engagement. Social engagement in terms of furthering or insinuating,

I don’t know if it’s a juster society, but a society maybe

less goal-oriented. I was always sort of attracted to that.

As I kid, I liked Goya’s drawings a lot and his artwork. And

all the pop artists who used sort of low end cultural output and

daily imagery for something that was worthy of aesthetic wonderment

and all that. Diego Rivera and a lot of Brazilian artists, Candido

Portinari. My brother studied art and he’s older so he would

have these books and he’d make me guess who did what painting

in his books. So, I had this baseball card exposure to European

art as a teenager. And then coming here and studying at the Art

Institute, I was much more interested in transgressive art or art

that makes the daily life tamper with this special temple of artmaking

and performance art, like Chris Burden and others. There are many,

many artists that I really like and admire but a lot of my daily

experiences here has been more with peers, like Scott Williams,

Barry McGee, Nao Bustamante, Manuel Ocampo, Sue Coe, Julie Doucet.

I also particularly like art from people who are not necessarily

participating in the high end art world, like Creativity Explored.

And also some of the older muralists here in town who relate the

Chicano experience, like Ray Patlan, Juana Alicia, Chuy Campusano.

It’s always been sort of a busy constellation of people rather

than this or that model.

The model that appealed the least to me was the Jeff Koons kind

of model in which people entered the artmaking process from a, at

the beginning he worked in the stock exchange, very sort of cerebral

and cynical, top down heavy way. My parents are both very sensitive

to art and appreciate the little things. But we never really went

to museums or galleries growing up. There were few; it’s a

very small town. But I think it would sound to me like a failure

if I was so engaged in an area of art making that I knew my parents

would, were I not their kid, not go check it out, or see it or connect

with it. That is what I strive for with my work, to have, making

a comparison with a building, many many doors, many ways in and

not requiring a whole set of pre-learned codes. And I’ve actually

done a little collaboration with my mom [namely embroidery] and

my father always encouraged us to draw. So that’s one of the

reasons why public art and mural painting started appealing to me.

It was the fact that people would encounter it in a situation that

was free and accessible.

|

| The

Mural Scene in San Francisco

Murals have been described as "art

galleries of the street", "mirrors of the community"

and "walls with tongues" that are really speaking to people.

What is the value of murals as public art? What are some of the

special benefits and challenges of a mural outside in the public

arena as opposed to having a painting or mural inside a gallery?

Once all the conditions that are necessary for an artist to have

studio space and studio time are met, the studio is a very free

place, a remarkably free place. Painting something on somebody else’s

building is rarely going to be that free. I think the vitality,

the diversity, richness, interest and worthiness of murals depends

from place to place and from period to period. What I think I’ve

witnessed in my time here is somewhat of a fossilization of the

form. It seems that there is not much trust from people at large

and the artists. People don’t realize murals are put through

a whole lot of bureaucracy and criteria to meet and so often times

you’ll see a mural and you’re like "Why didn’t

they do something a little more creative, a little more daring?"

And a lot of times it’s because they couldn’t you know.

And so I know for a fact that we could have a much more diverse

visual landscape in the City if we lived in a different kind of

city.

Do you think that’s particular

to San Francisco or is that something that is happening in other

large cities with murals such as Los Angeles or New York?

I would think it’s similar in other cities. Maybe here it’s

smaller, so it’s more micromanaged . I think in places where

property is not as valuable and where the management of property

is not as efficient, that maybe it’s easier. You might have

a building, but it’s in a dispute by 12 inheritors and nothing

is going to happen for 15 years. Those kinds of situations don’t

happen here as much as in other places. But, maybe there’s

just a gut pleasure about seeing some communications other than

corporate advertising. I actually was just thinking about that today.

I was thinking that maybe the mode of communication that most people

are most accustomed to having to deal with and have developed the

most defenses against is advertising, like commercials, especially

people who watch a lot of TV, but also on the street. It creates

the mindset in the public that basically we are being lied to all

the time or if not lied to, teased, manipulated, driven to excitement

about something which we know in reality is not quite that exciting.

Like picking up a phone, or being stuck in traffic, drinking a cold

beer, whatever. I think that actually leaves quite a heavy residue

in the way people are. For instance now, where we have a political

system where a president and high ranking politicians clearly are

lying to people and misrepresenting things. It’s hard to be

shocked or outraged at being lied to and having the world misrepresented

to you when that’s the thing you’re most accustomed to.

It’s quite nefarious in fact, and dehumanizing. So on that

basis alone, it’s so nice to be going down the street and seeing

the word "heart" on a wall. There’s a guy in town

who writes "heart" in his work and it’s just so nice

to see because that person is not about to benefit financially from

what he’s doing. He’s doing that because he is really

compelled to get his message out and it’s sort of an honest

voice amidst all this mercenary bombardment. So I think some of

my work has those kind of concerns in mind. Using an urban language

to point to natural features and natural phenomena.

It’s kind of like a lot of your

South of Market stuff, like Extinct, Sky/Ground, Innercity Home

and One Tree. I know there’s so much advertising down

there. What was your message behind those murals and how do they

compete with all the billboards and advertising around them?

They were meant as sort of pauses, respites from those other messages.

I also like to use humor. In a way, they are very simple, just statements

of the obvious. The messages are very loud and in your face, but

then they are not pushing anything that specific. So it’s like

asking for people’s attention and then letting them occupy

their attention with their own thoughts, their own triggers. You

can invite them to think with themselves, faced with a tree, sky,

ground, birds, or something simple. I think it’s just helping

make visible things that are obviously here but are not mentioned.

It’s letting people think what

they want to instead of telling them what to think. People can take

what they want from it and go in their own direction.

There’s only so much creativity available to people. And so

many people put their creativity to use in advertising that you

know, it’s hard to tell the difference. Ads resemble art more

and more. It’s so fast. Some advertising is using a language

that is so sophisticated that they are not even telling you what

to buy. It’s as sophisticated as any art production, so I just

try to keep it simple and keep it within context. I think it disappears

if it’s contextless. Different objects mean different things

in different places. A bottle of water in San Francisco would not

be a big deal, but a bottle of water in the middle of the desert

would be a huge deal.

You were talking a little bit about

globalism earlier and I wanted to ask you what kind of effect does

the fact that we can communicate much more easily than we could

maybe 50 and 25 years ago have on people? We have this incredible

cross exchange of products, people and ideas, but at the same time,

that brings with it some difficulties and challenges. How does that

affect your work?

I think it has a profound effect. Like I was saying about murals

before, they are very context specific because they are attached

to a building. They are very different from a work of art in a museum.

It’s a very different sort of experience. It’s not better

or worse, but just different. I think that I have put myself through

being in different contexts to try and internalize some of this

experience that is intrinsically temporary, like being able to move

to different places. It’s great. I am able to travel, but a

lot of people still live in a very different time. I’ve tried

to internalize that as much as possible, by spending time in the

places, meeting the people from there and I think one of the effects

that it has had on the work is throwing me for a spin. It really

makes me doubt where my priorities should be. So I’m proceeding

in a very confused manner. No shortages of impulses to make or interest

to make, but sometimes I’m not so clear as to where to put

the effort. But I welcome that confusion in a way versus as if I

were just reading, watching TV or being part of an established international

system of communication where I wouldn’t retain a sense of

control or an overview. People say once you leave one place, it’s

hard to stop leaving. What I’m finding is that also there are

some basic things that are just very much the same way everywhere,

you know things that people treasure, things that are agreed to

be good or not good for everybody. The experience of eating McDonalds

in Taipei or eating McDonalds in France might be interesting for

the sake of being in the same place but in a different environment,

but I think ultimately it’s weakening, debilitating. Fields

that only have only one crop tend to be more easily subject to plagues

or infestation or floods. Now we have Guggenheims, like Guggenheim

Bilbao. They are franchising that high end culture. They show the

same handful of artists, but they are not necessarily the most relevant

ones. They are not bringing wealth to a vast world but weakening

the diversity of it.

In

1993 along with Aaron Noble, you were one of the founders of the

Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP) which was a reclamation project

focused on a small Mission District alley. This project filled a

once shunned alley with dozens of striking murals done by various

artists with different themes and styles. What was the significance

of this experience on your work?

The Clarion Alley Mural Project is a particularly important project

for me because of the total involvement in community life it represented

for me, and still does, as well as for many artists in the Mission

District. As a founder of CAMP, it was amazing to witness the transformation

of the alley and the neighbors. We transformed from the house with

the nerdy characters and wild parties, to the house with nerdy characters

with names, shit scoopers, hoses, flyers, information, permits,

paints, artists, poets and even bigger parties. Clarion Alley went

from a path most avoided to a path much traversed. We were proudly

straddling the space between Mission and Valencia Streets, between

the heroin and crack pharmacy servicing mostly war veterans, prostitutes

and junkies, and the state-of-the-art new police station servicing

mostly the neighborhood’s youth and poor.

The diversity of the people served by this project was really a

trip. It was in the very real face of Clarion Alley that Aaron Noble

and I decided to warehouse the American superheroes of our youth.

America in the nineties was no place for escapist fantasies, at

least not on the street. You were bound to get physically caught

first by addiction and the police, than to successfully escape to

anywhere nicer. We didn’t want to escape, but wanted to share

our fantasies. CAMP to this day remains a particularly real, shared

fantasy. Thank you Balmy for all that you taught us. |

Extinct

RIGO 96

Sky/Ground

RIGO 98

Innercity

Home

RIGO 97

One Tree

Clarion Alley

Mural

Thinking

of Balmy Alley

RIGO 00

|

| Do

you think that you will stay in San Francisco? Why do you continue

to stay here?

Part of it is has got to be that it is still a pleasant experience.

I think now I feel more the need to spend time in other places as

well. I think that the 15 or so years that I have been here, I haven’t

seen the diversity of the City really deepen. As the City has been

growing, it feels smaller somehow. It’s an odd feeling. It’s

growing in the way of more franchised business, and this professional

class. They are the ones who have the skills necessary to make it

in a more demanding urban setting. They have their priorities clear.…

Just look at the difference between what’s going on now [in

Afghanistan] and the Gulf War 10 years ago when tens of thousands

of people had nothing better to do than be out in the street getting

arrested and protesting. It’s obvious now, myself included,

that people have less time dedicated to making sure they get to

express their ideas.

One of the first identities of the City that was presented to me

was this notion of a sanctuary town, people escaping political persecution,

sexual persecution. It was sort of like if you ran out of places

to go, you could still try San Francisco and maybe you wouldn’t

be too much of a weirdo over there with everybody else. And that

was nice. I got to meet people from Guatemala that were literally

running for their lives. A lot of times it was this paradoxical

thing of running from or dying in the guerrilla wars in their countries

and coming here, here being a safe haven, but then some of the reasons

why there was war in their country was being fomented by foreign

policy here. So it really reinforced this thing of San Francisco

as being a special corner. That is one identity and also there is

the identity of the right place to be for the most cutting edge

technology, like the place to come to get rich quickly; sort of

a new gold rush. So that’s a big shift and it’s already

started changing from that to something else. So I don’t know,

answering your question I guess, partially it’s inertia, friendship,

ties, and some things going on here. But, at the same time, there

are also a lot of my peers who have left. San Francisco remains

a very transient city. That’s exciting in a way, but the historical

knowledge of the City is not very deep; a lot of people have only

superficial knowledge of the City. |

Murals

and Politics

You mentioned Diego Rivera a little

earlier on in the interview. I wanted to know what you thought of

his work and the legacy that Rivera, along with fellow Mexican muralists

David Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco, left to the U.S. about the

intertwining of public art and political commitment. In Rivera’s

1940 mural at City College entitled Pan American Unity for

example, there is a whole panel dedicated to the fight against fascism

in World War II. What do you think about Rivera and this idea of public

art and political commitment?

I think that this is very much why Rivera was so appealing to many

people. Also, his personal trajectory of going to Paris and living

with all the other artists during a very intense cultural period.

And feeling that he could do that. But for some reason, it seemed

like as he got into it, he ended up running back to Mexico and asking

"Who am I?" and "Where am I from?" I find that

very interesting that he came back to try to find out more about culture

on this side of the Atlantic. I find a lot of righteousness in that

position. Making a stance for beauty in the actual world. One can

argue that making art and beauty do not necessarily have things in

common, but I think there is an overlap there. I very much feel like

that. I think that it’s hard to raise absolute notions of beauty

while not being valued at all by the system. I am moved by people

that take the time to pursue beauty.

I think the notion of intellectual commitment, like ideas about how

society should be shaped, are more common outside the U.S. than in

the U.S. Probably even more so now. In Europe and Latin America, you

have poets and novelists running for presidents of nations. Elections

come up and people are like, "What do intellectuals think?"

It’s something that does come to mind there and here not much.

Maybe it’s a generational thing. I think it’s very healthy.

Like the case of the three American athletes who put their fists up

when they won the gold medal at the Mexico City Olympics. Images like

that for me are very, very moving. I think that San Francisco has

some of that aura, you know that someone like Tom Ammiano is the president

of the Board of Supervisors. He’s someone who is clearly out

about his sexuality as a gay man and of all things, he was responsible

for the education of little kids and he is the president of the Board.

It’s a cool thing. It’s a nice, nice thing in San Francisco.

I remember seeing a debate about abortion in the Gay Pride Parade

and a group of very flamboyantly dressed gay men with a banner saying

"Gay Men Care About Women’s Rights." This kind of selfless

involvement in others peoples’ causes seems something very sort

of characteristic here. Something that for me is an essential thing

about San Francisco that I really enjoy. I think that it’s less

visible, less mainstream. |

Following

up on the Diego Rivera political question, you have done a couple

of different projects about the former Black Panther Geronimo Ji Jaga

(Pratt) and Native American activist and artist Leonard Peltier. What

is your interest in American political prisoners and how did you get

involved in their cases?

I guess it stems from personal experience in Portugal again during

that period of sudden political change. And some of the heroes of

that change there became political prisoners not too many years later.

And me and some of my friends visited them. They didn’t fail,

they were heroes, and then society changed and they again were too

off center or something. Experiencing the kind of personal freedoms

that I saw on the streets here, and when I heard about Geronimo’s

case, maybe I guess I was naïve, but it was truly shocking to

me that this could be going on in California. So while I was trying

to make art about something else, I would end up drawn back to that.

I first came in contact with his case through a little blurb in a

weekly paper, the [San Francisco Bay] Guardian maybe. Then

in ‘94, I did a mural in Oakland where part of the mural was

a portrait of Geronimo, for a project I did with children, innercity

youth who were basically getting paid to stay out of trouble for the

summer. It was my job to do something with them, so we painted on

the side of this thrift store and I did a portrait of Geronimo and

it said, "Geronimo Pratt, still innocent." We got in trouble

for it and I had to paint out the "still innocent" part.

Then years went by and Geronimo’s still in prison and I had a

chance to do a show in the Richmond Art Center in ’96 giving

the history of Richmond and the heavy African American population

that was invited to come there to work on the liberty ships and then

were sort of abandoned after the war. It seemed like a good place

to do something on his case. So I did an installation there called

Time and Time Again which just focused on his situation. It

was mostly just sharing his story. It wasn’t really an opinionated

presentation; the fact that the story was so powerful, it sort of

told itself. So I didn’t even really call him a political prisoner

and things like that. I just presented the years that he had been

in prison and said his time will come again. We corresponded and by

this incredible twist of fate, Geronimo ended up being released in

1997. And at the time, I was installing a version of the same show

in the Watts Community Center. So he came out in early June, 1997,

and the show was opening on July 4th, so he actually came to the opening.

It was very, very amazing. The whole thing was very special. The opening

was the night of the Mike Tyson-Holyfield fight and Geronimo, being

such a prominent member of the African-American community, was just

being bathed with thanks and appreciation and had been given ringside

tickets for the fight. Somebody had told him that our opening was

happening, his sister lives in Watts or something, so we get a phone

call at three in the afternoon the day of the opening and the director

of the center said, "Hey, we got a phone call. These people asked

if we could find Geronimo a TV here and if we get him a TV, he’ll

come to the opening." So she told me that, "You tell them

we’ll have the biggest motherfucking screen in the ghetto and

it’s gonna be free. Fools can stay home and pay thirty bucks

to see it on TV or be here for free and hang out with a bunch of Panthers."

And so it was. They had this gigantic video screen. It was quite nice.

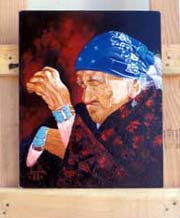

One of the experiences I am most thankful for here is the contact

with native people of California. I had been aware of Leonard’s

case for a little while. I decided to do work drawing attention to

his case partially as following up on my homework from the project

with Geronimo. So in the show in Watts I already had a section dedicated

to Leonard. This next thing happened when there was a show at the

De Young on how different Bay Area artists work and the role of museums

in the future. That’s where I did the Tate Wiki Kuwa Museum

which was a museum dedicated to showcase Leonard’s artwork. I

did these letters for the Tate Wiki Kuwa Museum that are the

same size as the De Young Museum’s letters. They were on the

side of the building and that’s such a powerful word "museum",

and using it for a different purpose. So I did that project with Leonard

mostly through his defense committee; the contact wasn’t as direct

as Geronimo. It’s very, very heavy and emotional. So for one

year, that was a lot of what I was doing. The project was in Berkeley

in ’99, then the show at the De Young and from there the show

traveled to London. And from there I took it to Santiago, Chile where

I hooked up with the Mapuche group there, an indigenous rights group.

So that’s been the extent of that work. It was spreading the

word a little bit to a few more people about who he is and what his

predicament is and also helping show his artwork, because he’s

an artist who works out of prison. Which again to me is a very encouraging

and moving tribute to the healing power of art. I really think that

art is good for people. You know it’s like running, like sports

is good for everybody. You don’t have to be Michael Jordan to

benefit from sports. Of course, some people are incredible to watch

what they do as long as you know everybody has their own level. But

it’s the fact that, confined to a small cell in those living

hell conditions, Leonard still finds some peace of mind to paint and

that his artwork is so celebratory and peaceful; it’s not accusatory

or even angry. It’s been painful and not easy to embrace that

this clearly has made my life richer.

Do you think that you’ll go back

to Leonard’s case in the future?

I think so. I always feel like I’m not doing enough. It’s

such a difficult period because there’s such bigger dramas unfolding,

so it’s a particularly difficult time for all. But yeah, I will

definitely continue to contribute to Leonard’s case. I just got

these letters back from a supporter of his. I think next year I will

probably organize a show of his art in Geneva. I’m still building

contacts there.

We have been referring in our emails

to the events that have been happening in Afghanistan the past few

months and I wanted to know if you have any comments on that. I’m

sure it’s affecting you and affecting your work on a daily basis.

I think that I am feeling this time more isolated than before. I have

a sense that there are a lot of like-minded people not knowing that

there are this many like-minded people around. I think a lot of people

are feeling, myself included, challenged by how to respond. I’m

still thankful for the fact that there is still a dissenting voice,

but it clearly doesn’t feel like enough. The more gut level or

basic thing that it has made me feel is that smaller is more manageable.

It just seems that it’s so hard to feel like one can have an

effect. I think education is very important, sharing information,

but I also feel like we need some creative ways to manifest a humanity

different from now. I think the part that’s hardest to get at

is the notion of personal sacrifice. I think it’s really hard.

In a way, I think that people feel betrayed by the world. What comes

next is not obvious. There are some things that I thought about before

like, "Ok, I’m going to make room for more of myself within

this and work within." But by benefiting as much as we do from

the same policies we disagree with, I think it will take some kind

of tangible, symbolic or otherwise gestures that we can call personal

sacrifices in order to speak out. I think it’s very important

for people who are here to communicate to people outside of here,

that we don’t all feel the same way about this. You know I was

disappointed to see that the only thing that has happened yet is you

see people raising money for the victims of the World Trade Center.

It hasn’t gone past that or behind that. Locally it has you know.

Michael Franti spearheaded the beautiful job of leadership in that

regard. That was a great concert in Precita Park soon after the U.S.

started bombing Afghanistan. It felt good to be here and it was a

real nice thing. In a couple of days, they organized it and 3,000

people showed up and it was a good thing. I think it will be interesting

to see what kind of art comes out of it.

|

Geronimo

Time and

Time Again

RIGO 96

pushpin on wall

Tate Wikikuwa

Museum

RIGO 99

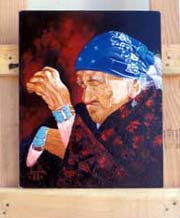

Elder

oil by Leonard Peltier

|

The

Future

What is your dream project? Is there

something that you haven’t had the chance to do, whether it be

not the time nor the place? What’s one area for the future?

I usually go from one thing to the other. I don’t have per se

these long set goals. But one thing I would like to do would be to

help facilitate a show of Native American art in Portugal. It’s

a hard question to answer because there are so many things….

I know that the question is probably something more about my own work.

Actually this project, the tricycle thing, I guess one thing that

has not happened for me yet is to create an art project that becomes

something that is self-sustainable.

On a much more serious note, I would like to be able to facilitate

or be part of a process that involved the gathering of people together

to see Leonard’s artwork which could remain all together and

be seen by many people. It’s not something that right now I can

say that I am right this month working towards it. It’s an idea

to be.

You recently had a show in March 2002

at the Gallery Paule Anglim. Can you tell us about the work you presented

there?

The show was from March 6-30th and included new works involving pushpins,

which I have used a lot before, and also commercial printing techniques.

Lunatics and Other Imperialists was there too. [Gallery Paule

Anglim is located at 14 Geary Street, San Francisco, (415) 433-2710.]

|

You

have been working on another mural TRUTH which is to be dedicated

in April 2002. What is the message behind this one?

TRUTH is both an ad and a request; a scream and a memorial;

an elusive reminder. In these, as in any other times of war, truth

is hard to come by. In America’s current war, the Pentagon broadcasts

untruths in order to get world opinion to come closer to the Americans’

self-image. This, of course, can only be accomplished through long-term

indoctrination or condensed spurts of carefully constructed untruths

that lead to 5 plus 17 equals 4.

The mural TRUTH complies with Dr. Dre’s intimation that

"this should be played at high-volume, preferably in residential

areas." The mural announces the notion of truth as a product

at high-volume specifically in a political area.

[TRUTH will be dedicated on Monday, April

22nd at Civic Center’s U.N. Plaza in a ceremony from 5-8 p.m.

The mural is dedicated to human rights activist

and "Angola Three" member Robert King Wilkerson. Wilkerson

was released from the Louisiana State Penitentiary in February 2001

after serving 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he did

not commit.] |

BIO

Siobhan Fleming teaches ESL at the Academy

of Art College in San Francisco. In addition to beading and photography,

she also gives free public mural walks for the volunteer tour organization

City Guides (schedules at

www.sfcityguides.org). |

|

|

|

|

|